Develop assessment practices that support, sustain, and measure student learning.

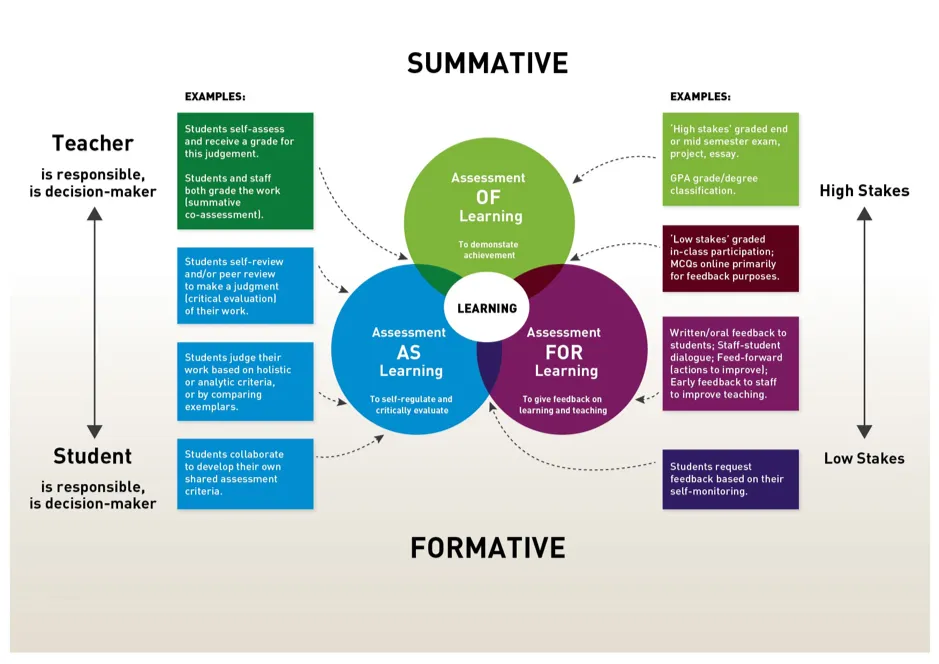

In this section, we dive into the importance of assessment and feedback as learning opportunities for students. The image below helps ground our definitions and understanding of assessment and how it can function in different classroom contexts (Assessment OF/FOR/AS Learning, 2017).

Purpose of Assessment

- Assessment should align with your course learning outcomes, objectives, and goals. Utilizing a backwards design approach where you start with the question "What do I want students to know/be able to do at the end of the course" and designing assignments from there can help you explicitly state what you are measuring and what feedback students need to achieve that goal.

- Transparent feedback can help uncover the hidden curriculum for students by explicitly connecting it to learning outcomes and instructor expectations.

- As students maneuver between different disciplinary and learning contexts you can help them "decode" by naming specific expectations to help students transfer learning.

Summative v. Formative Feedback

- Summative feedback focuses on the product of learning after an assignment and typically happens at the end of the semester or on a polished draft.

- Formative feedback focuses on the process of learning and happens throughout such as on student drafts, discussion posts, reflections, etc.

Low-Stakes Assignments v. High-Stakes Assignments

- Low-stakes assignments, or Writing to Learn, enable students to practice, process, and demonstrate understanding of a specific course element or content. They usually have a lower percentage of the grade and/or are ungraded. Feedback is formative focusing on the process.

- High-stakes assignments are usually large-scale projects with multiple scaffolded elements, typically represent a higher portion of the grade, and demonstrate learning of a wide variety of skills, tasks, and course content. Feedback is frequently a mix of formative and summative.

Teacher v. Student Conducted Feedback

- Teacher-conducted feedback is when the teacher or instructional team is the driving decision-maker and/or the primary feedback giver. Examples of teacher-conducted feedback are final grades and rubrics designed and filled out solely by the teacher(s).

- Student-conducted feedback is when the student is the driving decision-maker and/or primary feedback giver. Examples of student-conducted feedback are peer review and self-assessment.

Examples of Assessment Tools

Rubrics are tools shaped by the purpose of assessment from formative to summative. In this section, we will use examples to break down what three types of rubrics and what they can offer to the assessment process in your class.

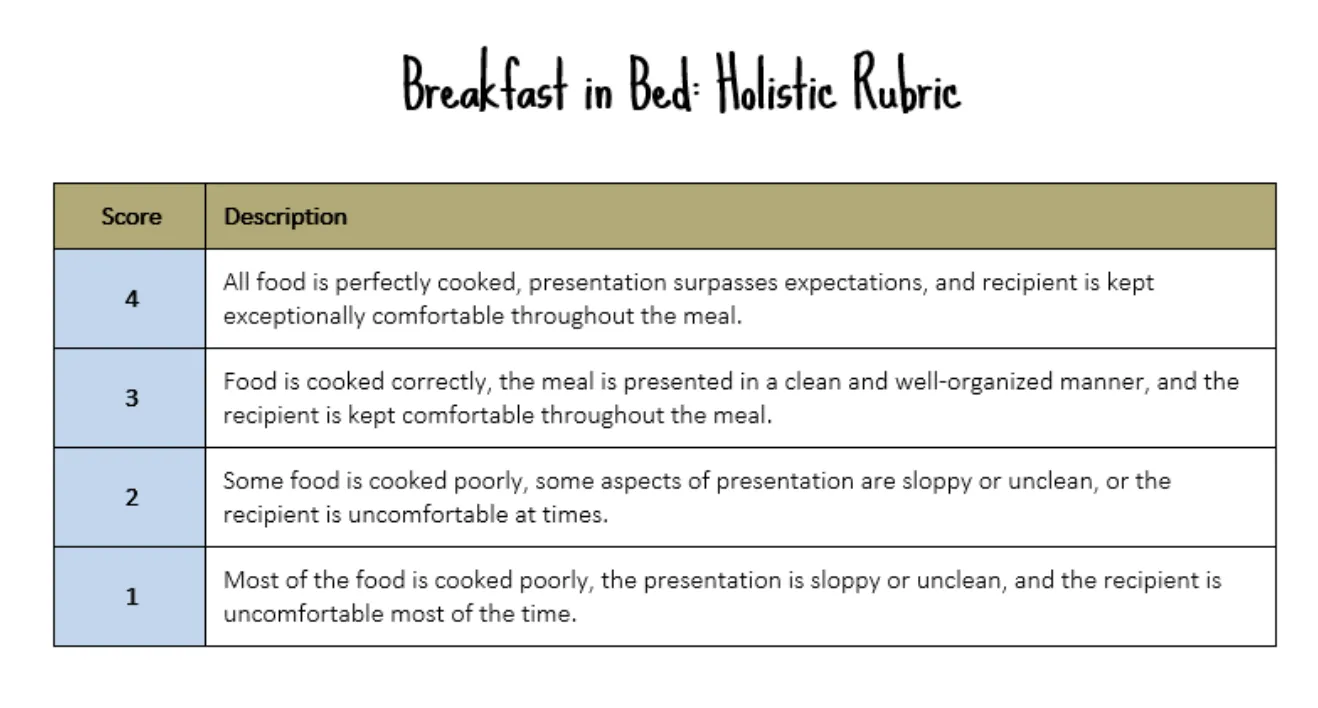

1. Holistic Rubric

A holistic rubric consists of three to five levels of performance, with a description of the characteristics that define each level. Each level of performance will include all criteria to be considered together (e.g., clarity, organization, format, mechanics, etc.). Creating a holistic rubric and grading with one is going to be faster for the instructor/instructional team. However, instructors won’t be able to provide targeted feedback to students as they will assign only one single score based on an overall judgment of the student's work, without breaking it down into separate qualities.

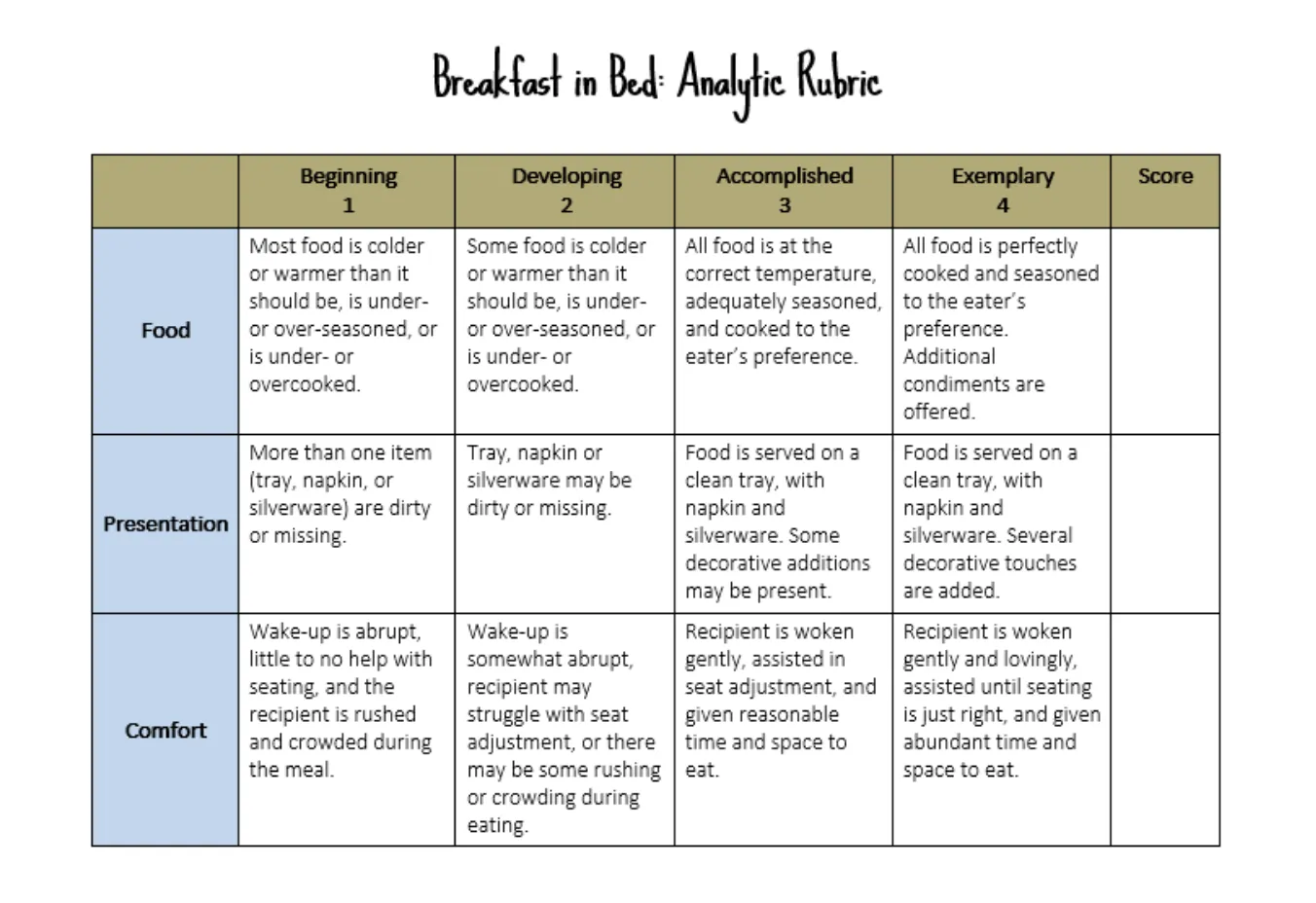

2. Analytic Rubric

An analytic rubric breaks down the characteristics of an assignment into parts, allowing instructors to provide useful feedback on areas of strength and weakness. In addition, criteria in the rubric can be weighted to reflect the relative importance of each dimension and students will understand exactly what their level of performance looks like. While an analytic rubric can be helpful for students learning, it takes more time to create and use it meaningfully.

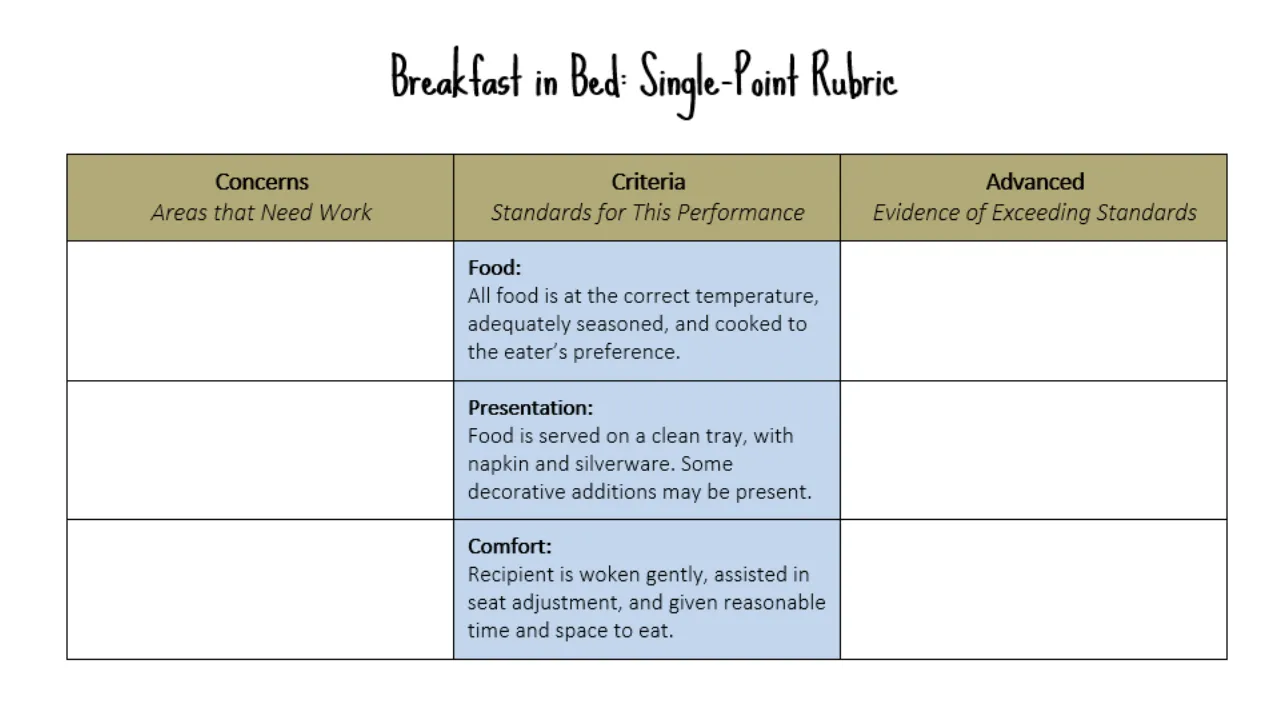

3. Single-point Rubric

Like holistic and analytic rubrics, a single-point rubric breaks the aspects of an assignment into categories, clarifying to students what kinds of things instructors expect of them in their work. Unlike those rubrics, a single-point rubric includes only guidance on and descriptions of successful work. A single-point rubric allows for an open-ended approach to both areas of concern and excellence, and in turn, also allows students to focus on the feedback without worrying about the grade on each category. However, this type of rubric can require a lot more writing on the instructor’s part.

In the creation and use of your rubric this time around, we also want you to consider some of these ideas:

- Not all writing needs to be graded — don’t be afraid to use Writing to Learn activities and completion grading.

- Not all writing needs to be assessed by the instructor — peer review feedback and self-assessment are incredibly generative modes of evaluation and reflection.

- Focus on content, organization, rhetorical situation, articulation of main ideas, use of writing to explore the topic, and incorporation of evidence.

- Define evaluative criteria in ways that are usable, not just “clear”. Your students are users of these documents.

- Reduce emphasis on grammar and mechanics. Studies in our field show such feedback is less helpful for student writers’ development (and can stunt growth).

- Make note of patterns of error — don’t mark everything. Students learn best when only one or two patterns are identified, accompanied by an explanation of why the “error” matters or is important.

- Read student work more generously. When we read for an error, we find an error.

- Include students in the rubric process -- having them help develop criteria, clarify terms, or use the rubric during Peer Review.

Resources:

Know Your Terms: Holistic, Analytic, and Single Point Rubrics by Jennifer Gonzalez

Peer review refers to the many ways in which students can share their work with peers for constructive feedback and then use this feedback to revise and improve their work. For the writing process, revision is as important as drafting, but students often feel they cannot let go of their original words.

Key components of effective peer review include encourage reflection, differentiating between a reader (describe and suggest) vs. an evaluator (judge and correct) mindframe, providing modeling and examples, allowing for feedback on the peer-review process and having multiple opportunities throughout the semester.

Creating specific peer review prompts helps students concentrate on providing meaningful, content-driven feedback that is useful for revision. Here are a few guidelines for creating peer review prompts to help students focus on big-picture issues:

- Emphasize the role of peer reviewer-as-reader. Create prompts that ask the peer reviewer to respond to the writing from a reader’s perspective.

- An example prompt might be: Read through the lab report once in full. In your own words, summarize the research question and primary findings.

- Align the peer review prompts with the assignment criteria and learning objectives. Create prompts that help peer reviewers provide insight into how the writer meets these in their work.

- If an assignment objective is to compare and contrast the State’s use of war during two different historical periods, an example prompt might be: Identify one contrast the writer made between the two wars they researched and explain how this contrast added to or clarified your understanding of the relationship between the State and war.

- Prioritize and limit the number of peer review prompts so students can devote more time to providing quality feedback on a few aspects. Create peer review prompts that elicit feedback on how the writer accomplished specific aspects of the assignment.

- An example prompt might be: Identify one place where quantitative data provided clear evidence for the writer’s claims. Identify another place where the use of quantitative data is confusing or does not support the claims. Explain how these uses helped and hindered your understanding as a reader.

Here are our recommendations for setting up and facillitting peer-review in your class.

Before Peer Review:

- Plan the activity

- Establish goals and timing

- Set-up partners or groups

- Choose a tool (i.e. D2L, Google Docs)

- Assess the peer review

- Explain how you will assess peer review

- Prepare students

- Describe the reader vs. evaluator position

- Model feedback practices for students

- Encourage students to reflect pre-peer review (example: what do you want to get feedback on?)

During and After:

- Provide instructions

- Develop either verbal and/or written instructions

- Provide worksheet/guided questions

- Help students revise

- Provide reflection opportunities

- Assign revision plan, follow-up, etc.

- Give feedback on peer review process

Resources:

For more resources and activities related to peer review, revising, and editing, please view this document and UA Writing and Learning Project's Website on Peer Review.

Self-Assessment is a process in which students gather data about their own learning experience(s), analyze what it reveals about their progress toward their goals, and then plan next steps for their learning. In this section, we highlight some activities that can promote self-assessment in your class.

1. Learning e/Portfolio

This type of activity is a High-Impact Practice (HIP) and has become a vital way for students to keep records, curate documents and visuals, and learn organizational skills. Students gather artifacts of their learning along with written responses and reflections to provide evidence of their learning. Depending on the course, artifacts may include: images of notes, peer review documents, photographs, videos, screenshots, previous assignments (in draft or final form), transcripts of interviews, poster presentations, links to slides, podcasts, or completed projects. ePortfolios also include contextual information and a self-assessment of how effectively they met the learning objectives of the course can be a beneficial reflection exercise.

- For service-learning courses, e-portfolios could contain any of the following: service-learning contract, weekly log, personal journal, impact statement, directed writings, and photo essays. Include products completed during the service experience (i.e., agency brochures, lesson plans, advocacy letters).

- Learn more about ePortfolios at the University of Arizona ePortfolio website.

2. Journals

Journals may be written as private, individual journals with general prompts or prompts specific to the current lesson. Variations on the basic journal include methods of sharing and commenting done by peers. For the double-entry journal, students draw a line or divide their page in half, write a journal entry, and then a peer reacts and comments on the other side. In a triple-entry journal, students journal on their learning on one-third of a page, a peer responds in the second area, and the student then analyzes their own entry and the peer responds in the final third of the page.

3. Reflective Essays

To make the learning more personal, have students write a reflective essay. A reflective essay asks students to think critically about the course content, how they’ve learned about it, how their ideas have changed, and how they will apply it in the future. This assignment can take many shapes, but many prefer a narrative essay format (rather than a more free-form journal format). Prioritize incorporating critical thinking techniques and using supporting details from course content.

4. Feedback to Revision

Instructors take great care offering feedback on student writing or creating opportunities for peer review of works-in-progress, and can get frustrated when students don’t show improvement. However, research shows that the feedback alone will not ensure student success. Students need opportunities to reflect upon feedback and consider how they can apply the lessons learned to current and future writing.

Self-assessment is a process in which students gather data about their own learning experience(s), analyze what it reveals about their progress toward their goals, and then plan the next steps for their learning. Here are a few quick ideas for helping students self-assess feedback and apply it to a writing task:

- Ask students to read the feedback with an open mind. Try to understand what each reviewer was trying to say, and how the feedback helps you adjust your work so that it acknowledges different viewpoints in your audience.

- Allow class time to read and respond to feedback. Ask students to write a letter to the instructor or the peer reviewer responding to some (or all) of the following questions:

- Has anything confused you?

- What do you most agree with (if anything)?

- Do you (respectfully) disagree with any of my comments or suggestions?

- With the upcoming writing assignment in mind, what are specific areas of writing you feel you still need to work on? What strategies will you use to work on them?

- Encourage students to review prior feedback as they draft another assignment. Feedback tends to get left behind with the grade. Ask students to identify specific feedback to work on from their previous paper as they revise a current writing project.

- Make a revision plan. After a peer review session, ask students to make a revision plan that will be submitted with their final draft. This revision plan should include at least one significant revision (e.g., beyond “fixing” or sentence-level issues).

Like all writing activities, the ability to use feedback is learned over time and with lots of practice. These activities can be graded minimally (complete/incomplete) or offered as a percentage of a final paper grade to encourage the attention feedback deserves.

Adapted from: Ferris, D. R. (2015). Inclusivity through community: Designing response systems for “mixed” academic writing courses. In M. Roberge, K. M. Losey, & M. Wald (Eds.), Teaching U.S.-Educated multilingual writers: Pedagogical practices from and for the Classroom (pp. 11–46). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Resources

Strong relationships with students always start getting to know them and understanding their positions in the classroom through conversations.

Individual conference is a strategy where teachers and students meet one-on-one for a set period to discuss specific items, usually in the first few weeks of class, before a final draft submission, or one or two times throughout the semester to check in on their learning. By having conferences with students individually, teachers will be able to learn more about students’ needs, provide explanations or detailed feedback on their writing, or get feedback from students in term of classroom related issues. Students also benefit from knowing that their teachers support their learning and from there create a more trusting relationship.

Group conferences are a strategy where teachers set up students in different groups to engage in collaborative learning and to help each other develop their papers. When conducting group conferences, the role of the teacher will be to facilitate the conversations between students and their work, to allow students to learn from each other, and to answer any questions that arise during this time. Group conferences can also be used as a space for students in the same peer-review group to talk about their peer-review experiences and reflect on changes that they will make.

Depending on your purpose for having conferences, we encourage you to consider some of these tips:

- Prepare yourself and set a manageable schedule for each conference meeting.

- Prepare your students by talking to them about what they can expect from these conference meetings.

- Arrange a space to meet with students (in your classroom, in your office, via Zoom) so that they feel safe to discuss information with you.

- Before conference day, remind students about the conference and ask them to bring questions or comments regarding their peers’ work (if doing a group conference)

- During conference day, make sure to keep track of time and come prepared with notes on each student’s work.

- After conference day, set up a short reflection prompt for students to reflect on their experience so you can make changes for the next round.

While it seems daunting to add and assess writing in large enrollment courses, we encourage you to consider writing to learn content such as low-stakes (i.e. reflections, reading responses, etc.) or participative writing (i.e. in-class writing, collaborative writing) to allow students to see writing as a process of learning rather than just a product. By bringing in frequent yet short writing assignments, students can focus on using writing as a tool or method for exploring perspectives, building connections, and engaging in content in the course.

When it comes to grading writing in your large classes, we want to remind you that:

- Not all writing needs to be assessed/graded.

- Not all writing needs to be assessed/graded by the instructor (we recommend self–assessment and peer review).

- All low-stakes writing assignments (i.e. reflections, discussion, lab notes, journals) count as writing, and students can use writing to learn content without you grading everything!

As you assess writing to learn content, you can focus on content, organization, rhetorical situation, use of writing to explore a topic, articulation of main ideas, and incorporation of evidence (including reflection/personal experiences). We suggest that you don’t focus solely on grammar and/or style/tone.

In addition, depending on where students are in their writing process, feedback can be helpful! However, to be mindful of the labor you put into giving feedback, you can decide when and how to give feedback:

- Formative v. Summative Feedback: Formative feedback is designed to help students revise their work, summative feedback is typically for more polished work and connects feedback to assessment measures.

- Higher-Order v. Lower-Order Concerns: Higher-order concerns are more conceptual and structural such as content, evidence, and organization. Lower-order concerns focus more on grammar and mechanics.

- Modality of Comments: Feedback can take place in texts (such as Google comments), rubrics, at the end of paragraphs, through group/individual conferences, videos, whole class feedback, peer review letters, reflections, and/or a combination.

- Conversational/Invitational Tone: Using a conversational tone in comments provides students with the opportunity to ask questions, view writing as a process, and connect to their learning.

Resources:

We recognize that the assignment you had planned for your face-to-face might not work in the same way now that you are teaching online. Here are some suggestions on how to successfully teach and assess writing in online classes.

1. Have consistent and regular deadlines for asynchronous activities.

As you probably have already noticed in any of your classes, students are unlikely to consume (read, view, listen) a text unless they know they are then completing an activity that holds them accountable for that text. In addition, students will benefit from having consistent and regular deadlines and reminders for their asynchronous activities. We suggest that you not only make sure that students will be doing something with any required reading, video, or audio text (this could include recorded lectures or videos you make) but that you design the activity as a single prompt that starts with them reading and then prompts them with an engagement activity.

2. Discussion activities for students to interact with texts, and understand concepts or their writing assignment.

There are various ways to use discussions for supporting writing. It helps to estimate the time commitment. Then students understand your expectations. Below there are examples for directing online discussion of assigned readings and discussion posts focused on planning and sharing writing as a process.

Idea #1: Discussion forum for assigned readings, videos, performances, etc.

Discussion posts can be valuable tools to help students engage on a deeper level with various texts.

- A successful way to imitate face-to-face discussion is to have two deadlines for a discussion board: one for the primary post about the assigned reading/text and one for the secondary posts in response to other students’ posts (at least three responses are a good amount).

- For examples of what these activities might look like, for language to assign these activities, and rubrics to assess them, visit this document.

Idea #2: Provide a space for student questions

Students need a designated place where they can ask you questions about the assignment and see your answers to other student’s questions. If one student has a question, others often have the same question.

- Have a designated discussion post for the assignment where students can ask you questions. Direct students to this post when introducing the assignment.

- OR share the assignment promptly as a Google Doc with the commenting ability turned on. Have students ask questions by directly commenting on the part of the assignment that is confusing.

Idea #3: Individual writing process posts

Students can also use discussion posts to discuss the different stages of their writing process as they work towards completing an assignment. Posts can be about planning, researching, drafting, revising, reflecting, etc.

- It helps students engage in prewriting activities to gather ideas. Here’s an example that invites students to select an image that connects to their purpose in the writing assignment: Check out Example Activity 1: Select a Purpose.

- You can also guide students through a process by asking students to offer brief progress reports on their research and other types of planning: See Example Activity 2: Process Post

Idea #4: D2L Annotations

There is also a helpful tool built into D2L. It is available whenever you open an assignment from a student in D2L. To learn more about how to use the annotations tool, visit these D2L help pages.

Idea #5: Audio or Video Notes in D2L

When you go to evaluate an assignment in D2L, you also have the option of directly recording a video or audio note to students. In the sidebar, when you open an assignment, scroll down until you see the comment box.

4. Designing and Using Rubrics

Rubrics are an important tool to communicate to students our expectations of an assignment and also serve as a tool to remind us of what we want to focus on when grading.

Idea #1: Rubrics in D2L

D2L has a rubrics tool that can be very useful. You can connect it to the assignment folder, so students can view the rubric. For more information on creating a rubric in D2L, visit these help pages.

Resources:

- Possible digital teaching technologies (digital resources in multiple media that can be used in your classes; good information on captioning multimedia for accessibility purposes)

- Teaching with compassion and focus amid disruption (comprehensive crowdsourced collection of resources across disciplines on how to continue teaching in these unusual circumstances successfully)

- Quality Matters Emergency Remote Instruction Checklist