Writing is not only a product of learning but a process. Engaging in Writing-to-Learn supports metacognition, critical thinking, and transferable skills.

What is Writing to Learn (WTL)?

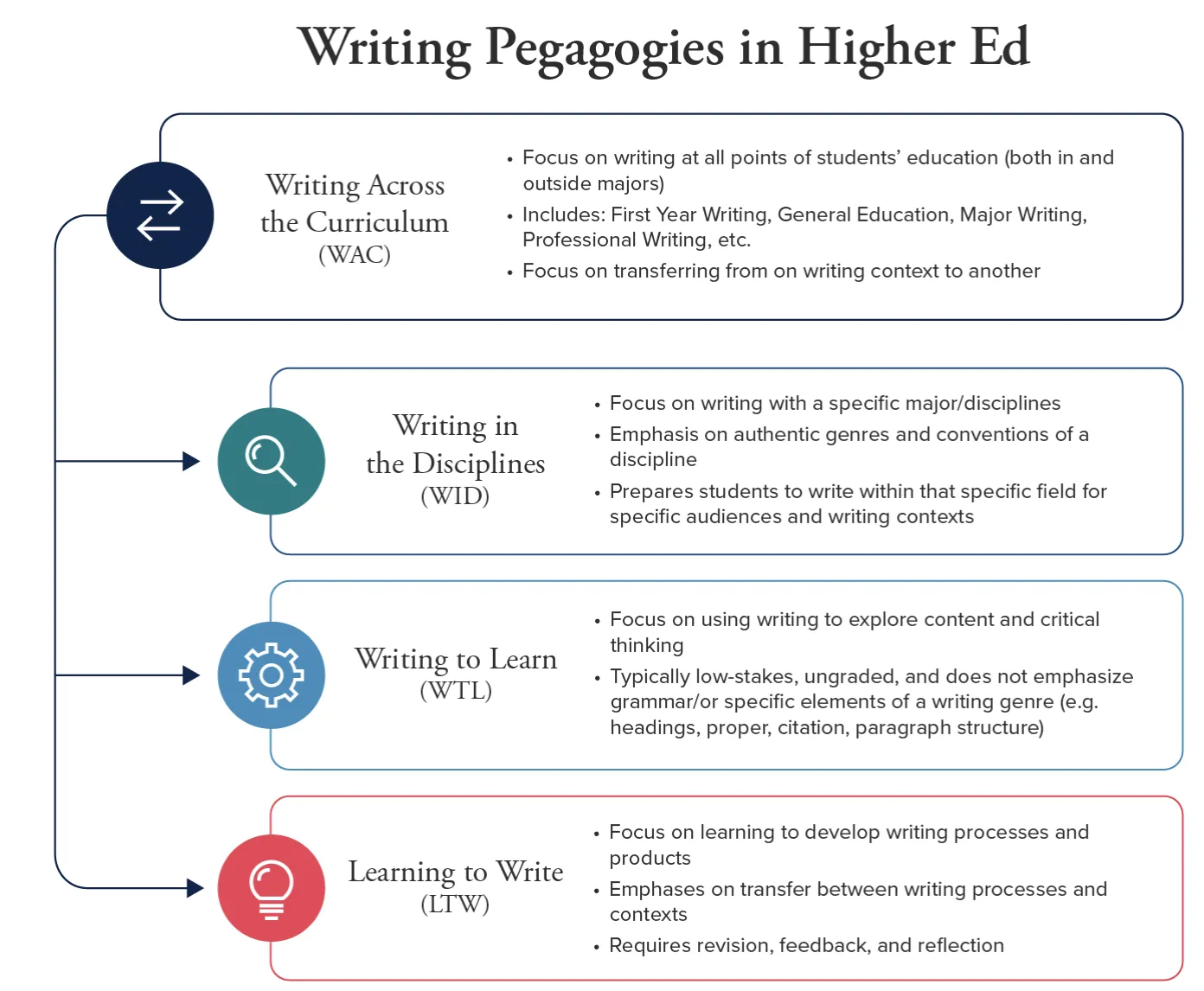

Within WAC there are three common branches of writing (Table 1):

- Writing in the Disciplines (WID) focuses on replicating and creating writing that is common for students’ majors or disciplines they are exploring (e.g. an NSF grant for a biomechanical engineering student or a business memo for a marketing student). Typically instruction focuses on creating these texts and feedback focuses on how effective students were in this type of writing.

- Learning-to-Write (LTW) focuses on the process of writing such as drafting, conducting research, finding sources, developing arguments, identifying audience and purpose, revising and editing, and other parts of the process. Typically instruction focuses on scaffolded parts of the writing process and are not bound by a single discipline and feedback focuses on achieving various learning outcomes related to process (e.g. finding appropriate scholarly peer-reviewed articles).

- Writing-to-Learn (WTL) focuses on using writing as a tool for processing, understanding, critically examining, reflecting, making connections, and playing. These are typically low-stakes assignments that happen in and outside of the classroom.

All three are important aspects of students’ writing trajectories throughout their college careers and frequently happen in all classes. We are focusing on WTL because there are many lists of activities but rarely specific prompts, unlike our WID and L2W counterparts. These WTL activities are especially important for students to develop belonging, connect their cultural backgrounds and knowledge, and develop metacognition (Venegas et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Writing Pedagogies in Higher Education

Grading: WTL activities are frequently ungraded or graded on completion. This is largely so students have a “safe space” to practice their ideas without fear of penalty and instead focus on idea generation. It also allows students to focus less on grammar and English “correctness,” which is especially important for neurodivergent and English language learners. Despite the absence of grading, instructors can provide (though not always necessary) whole-group feedback or feedback on different batches of student work each week, or focus on content rather than a set of criteria you would use for a LTW assignment. WTL activities can also provide opportunities for peer review or self-assessment. It is important to explicitly tell students how and why they will be graded a specific way.

Example of WTL Evaluation Language:

“To earn credit, your post/contribution must be substantial, respond completely to the above question, and be submitted by the posted deadline. Because this is informal, conversational writing, it will not be graded for surface correctness [specifically referring to grammar]” (Métris, 2020.)

WTL in STEM

WTL helps students in STEM to increase disciplinary belonging, transfer skills, and metacognition. This resource provides examples of WTL strategies and prompts from real classes at U of A.

WTL Reflection Activities

Reflection activities are a prime example of WTL that supports students in using writing as a tool to critically analyze their learning and the world around them. This guide provides example reflection activities instructors can draw on for different purposes.

WTL in Online Courses

WTL happens across all course modalities. This guide helps support online writing, including activities such as peer review, discussion posts, and annotating texts.